Software Assistant for Oncologists

At the German Cancer Research Center, HIDSS4Health-researcher Paula Breitling contributes to the development of a software that aims to help doctors recommend appropriate therapies. This could allow more patients to benefit from custom-fit treatment.

“No dissecting, no blood!”—this was one of Paula Breitling’s conditions when she chose her field of study. For her, data and information were the abstract objects that she found more fascinating—despite having an avid interest in life science topics. Now, the information specialist is demonstrating in her doctoral thesis that it’s also possible to save lives with data expertise rather than swabs or scalpels. Breitling wants her research to support doctors with the difficult task of providing suitable therapy recommendations for the treatment of cancer patients and offer more people access to personalized tumor therapy in the process.

She is a doctoral candidate at the Helmholtz Information & Data Science School for Health HIDSS4Health, which is part of the Helmholtz Information and Data Science Academy (HIDA)—Germany’s largest postgraduate training network in the information and data sciences. HIDSS4Health offers Breitling a unique mix of data science and medical research that is vital to a project like hers. Abstract data come together with a very tangible field of application here—oncology. “Cancer is an issue that affects many people—even if it is their relatives and friends who get sick,” says Breitling. She herself had direct experience with this while completing her degree, as one of her fellow students was diagnosed with cancer while they were preparing for their exams together. “If I am able to use my data science background to do something that helps people who are affected by cancer, I would find that very satisfying.”

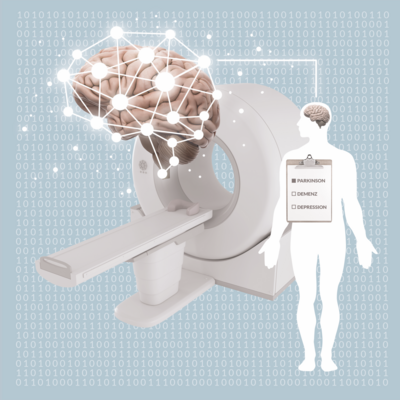

Breitling’s expertise in applying data science methods to structure large quantities of data comes into play where standard therapy approaches in cancer treatment are no longer effective and the doctors treating the patients have to seek other potential therapies. To do this, they need to assess complex information relating to the respective patients, because the biological characteristics of a tumor disease don’t just vary between different types of cancer but also from patient to patient.

"Cancer is an issue that affects many people. If I am able to use my data science background to do something that helps people who are affected by cancer, I would find that very satisfying."

Paula Breitling, Doctoral Researcher

AI for therapy recommendations

The first step in identifying other potential therapy approaches is sequencing the patients’ DNA. Looking at the genome makes it possible to see whether there are specific mutations associated with cancer. This can offer an indication as to whether certain combinations of drugs can be used. Oncologists provide therapy recommendations based on this data and other information relevant to the patient. Breitling says that experience plays an important part in this: “Some oncologists already know what direction they need to move in if they find certain characteristics; doctors who are relatively new to this field, on the other hand, have to spend significantly more time searching and verifying and have to throw out a lot of information.” Even an experienced doctor would need around two hours to complete this work, Breitling says, while it would take well over a day for a young colleague to put together a sound recommendation for just one patient. Making this process simpler for all doctors is the goal that Breitling is pursuing alongside other researchers. Her job is to capture the workflow that a doctor negotiates while making their decision, so she can then model this workflow with the help of a computer using data science methods and map it in a software solution.

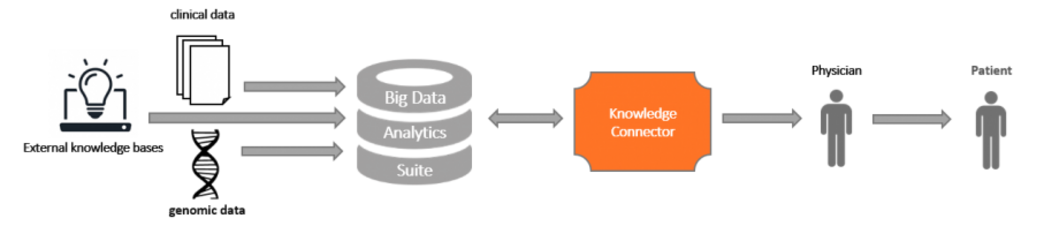

This software—the Knowledge Connector—is designed to connect all these different units of knowledge and is being developed at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg. Breitling’s own research project is split between this location, where she is a member of Frank Ückert’s team, and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), where she works on the other half of her project, data science, in Michael Beigl’s research group.

Software for all relevant information

The Knowledge Connector links various external databases and gives the doctor a clear overview of the collected information with respect to the individual characteristics of a patient and their tumor. Information on genetic variants, genome mutations, drugs, and various clinical studies and publications are incorporated into this evaluation process—a multifaceted task that doctors have had to carry out on their own to date. Based on all this information, it then becomes easier for the specialist to put together a ranking of promising treatment variations. And the tool can also highlight suitable drug studies that are currently underway and could accommodate the patients, for example. The software doesn’t put together any therapy recommendations itself—but, “ideally, applying this software would give the oncologist all the information they need to make their decision, and they wouldn’t have to do all the research themselves anymore,” Breitling explains.

The advantage of this type of tool is that it merges clinical and scientific data that is usually documented in different IT systems and isn’t generally suitable for being exchanged or analyzed in conjunction with other data. Using the new tool, doctors should be able to put together a list of the therapy recommendations based on the parameters that are deemed important and transfer them directly into the appropriate text form. This eliminates a lot of the work involved in copying and writing information, which eats up doctors’ time. It’s easy to see how this makes doctors’ work easier: they have a better overview, there aren’t so many different file formats, and a therapy recommendation can be put together more quickly. By making the workflow simpler, the software can ultimately play a role in helping more people benefit from personalized (and therefore more effective) treatment than previously.

"Understanding a doctor’s entire knowledge process"

A prototype of the Knowledge Connector is already in the initial testing phase. But the system is still far from being able to do everything doctors would need. Breitling is addressing this by looking at exactly what they do with the program: “We need to understand a doctor’s entire knowledge process,” she says. “In order to make an algorithm on this basis, I need to know, for example, how often they click, how often they switch to a different page, when text entered was where, and what search steps were carried out at what point in time.” It goes without saying that this isn’t done by peering over the doctor’s shoulder; these processes are recorded by machine. A simple piece of software that runs alongside the program stores data regarding keystrokes, clicks, and the websites accessed; it records the time spent on a website, text that is keyed in, and many other parameters. Vast quantities of data are created in the process. Breitling has yet to make any final decisions on the methods she will use to subsequently model these processes—but the young researcher can already pick up on certain weaknesses in the software when she takes a cursory glance at the vast datasets in her first test sequence. Her ongoing analysis will focus on the following questions: How do doctors conduct their research right now? How do they use the software? What other features does the Knowledge Connector need, and how should the user interface be designed? A total of nine oncologists will test the software at a later stage in the project—at least, this is what Breitling fervently hopes for, so she can soon have a broader database to work with.

Designing such an extensive study and organizing a multifaceted research process sounds challenging, but the eloquent doctoral candidate doesn’t find this daunting. For Breitling, even the demanding selection procedure that HIDSS4Health set out for its applicants motivated her rather than scaring her off: “I just thought, I’ll give it a try!” Out of nearly 220 applicants, eleven candidates were ultimately selected for the first cohort at HIDDS4Health—and Breitling was one of them. She is now happy to have the opportunity to benefit from an inspiring network and is taking her involvement a step further: As the spokesperson for the doctoral candidates, she represents their interests in the steering committee—and therefore also plays a small part in shaping the ongoing development of HIDSS4Health.

As far as her own research is concerned, Breitling is looking eagerly ahead to the moment when she finally has all the data she needs. Her enthusiasm is evident when she talks about her work: “Once you’ve actually got the data, you can do wonderful things with it!” For example, processing it in a way that ultimately makes it possible for more people than ever before to have access to cancer treatment tailored specifically to them. It’s medical assistance thanks to data science—without scalpels, but with a lot of heart and soul.

Author: Constanze Fröhlich